![]() The Journal of

Public Space

The Journal of

Public Space

ISSN 2206-9658

2022 | Vol. 7 n. 2

https://www.journalpublicspace.org

“We should all feel welcome to the park”: Intergenerational Public Space and Universal Design in Disinvested Communities

Gus Wendel, Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Claire Nelischer, Gibson Bastar

University of California, Los Angeles, United States of America

gwendel1583@ucla.edu | sideris@g.ucla.edu | cnelischer@ucla.edu | gibson.bastar@gmail.com

Abstract

This article investigates the potential for intergenerational public space in the Westlake neighbourhood of Los Angeles. Through a series of site observations, focus groups, interviews, thick mapping, and participatory design exercises, we work with 43 youth and 38 older adults (over 65), all residents of Westlake, to examine their public space use, experiences, and desires, and identify where the two groups’ interests intersect or diverge. We explore the potential for complementary approaches to creating intergenerational public space using the principles of Universal Design. In doing so, we emphasize the importance of taking an intersectional approach to designing public space that considers the multiple, often overlapping identities of residents of historically marginalized communities predicated by disability and age, in addition to race, class, and gender. Our findings yield insights for creating more inclusive and accessible public spaces in disinvested urban neighbourhoods as well as opportunities for allyship between groups whose public space interests have been marginalized by mainstream design standards.

Keywords: public space, disinvested communities, universal design, intergenerational public space

To cite this article:

Wendel, G., Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Nelischer, C., Bastar, G. (2022) “We should all feel welcome to the park”: Intergenerational Public Space and Universal Design in Disinvested Communities, The Journal of Public Space, 7(2), 135-154. DOI 10.32891/jps.v7i2.1481

This article has been double blind peer reviewed and accepted for publication in The Journal of Public Space.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial 4.0

International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

![]()

Introduction

Youth and older adults are typically not present in decisions about the built environment. This study examines the public space experiences of low-income older adults and youth in the Westlake neighborhood Los Angeles, seeking to make their voices heard and translate their needs and preferences into public space design recommendations[1]. Another aim is to explore opportunities for intergenerational public settings. Given the aspiration of Universal Design to create built environments that are “usable by all people to the greatest extent possible” (Mace et al., 1991:2; United Nations, 2016), we ask: How might Universal Design frameworks help create intergenerational public spaces in the context of historically marginalized communities?

Westlake is such a community; it is high-density, multiethnic, low-income, with high concentrations of children and older adults. Westlake has less open space per capita compared to the citywide average (0.84 acres/1000 residents compared to 3.3 acres/1000 residents (AARP et al., 2018)). Given the neighborhood’s demographics, its relative dearth of public spaces, and a global pandemic posing additional barriers to public space access, Westlake provides a good geographic setting to explore our previous question.

We begin by unpacking the literature on public space inequity and the importance of intergenerational Universal Design frameworks. This framing sets the stage for the discussion of our empirical study. We share our study findings and implications for design and policy and conclude with recommendations for creating intergenerational public spaces.

Socio-demographic Inequities and Public Space

Access to outdoor public spaces can provide health and recreational benefits to communities. However, the provision, quality, and safety of public spaces are distributed inequitably in many cities (Wolch et al., 2005, 2014; Boone et al., 2009; A. Rigolon et al., 2015a; Macedo and Haddad, 2016; Tan and Samsudin, 2017; Rigolon and Németh, 2018). This is true in Los Angeles, where 82% of the city’s park-poor neighbourhoods are in communities of colour (Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation, 2016).

In the US, these spatial inequities are outcomes of historic class and ethno-racial oppression, where patterns of state-sponsored segregation and disinvestment through redlining, urban renewal, and ‘white flight’ overwhelmingly impacted communities of colour (Byrne and Wolch, 2009; Byrne, 2012). Wealthier, predominantly white, suburban households had the resources to maintain abundant outdoor public space, while low-income communities of colour in the urban core had limited access to quality public space (Heynen et al., 2006).

Inequities

inscribed in the built environment are exacerbated among demographic groups who

face additional barriers to accessing public spaces. For low-income youth in neighbourhoods

with limited public open space, traveling long distances to access public

spaces or paying for private recreation facilities is out-of-reach (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2002). Similarly, low-income older adults

often rely on neighbourhood public spaces for

recreation and socializing (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2014). Both demographic groups benefit from increased access to public space, perhaps more so than other groups. For low-income older adults, particularly those living in small apartments without private yards, neighbourhood parks offer respite and opportunities for contact with nature, walking, and exercise. For children, parks provide formative learning opportunities through play and socialization (Author et al., 2002). Access to outdoor public space took on added importance for low-income individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic, who were disproportionately impacted by the virus (Low and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020).

Even if public spaces are available, they are often not designed or programmed to serve the needs of all children (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2009) or older adults (Loukitou-Sideris et al., 2014). The role of planners, designers, and policy makers in accommodating these needs is significant (Winick and Jaffe, 2015), in light of shifting demographics and widening income gaps in the US.[2] Scholars and activists have called for more inclusive approaches to designing the built environment, giving rise to the influential paradigm of Universal Design, which promotes design guidelines that benefit everyone, regardless of ability or age (Mace et al., 1991) and is central to inclusion and accessibility frameworks, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006), the New Urban Agenda (United Nations, 2016) and the World Health Organization’s Age-Friendly Cities Framework (WHO, 2007). But policy makers, designers, and academics have tended to overlook how public spaces might be designed to accommodate both children and older adults, much less low-income children and older adults, as well as others experiencing the intersection of multiple frames of oppression (Crenshaw, 1991). In the next section, we give an overview of recent literature that draws from Universal Design (UD) and intergenerational public space (IPS) approaches.

Intergenerational Public Space and Universal Design

Meaningful relationships are key to helping young people develop purposeful lives, and non-parental mentors can provide formative support (Carstensen, 2016). For older adults, studies have shown that caring for the next generation can lead to increased happiness (Vaillant, 2003), and that intergenerational volunteering positively impacts older adults’ mental and physical health (Tan et al., 2009). Motivated by these findings, researchers have increasingly recognized the need to support the health, safety, and wellbeing of city dwellers across the age spectrum, including children and older adults (Thang and Kaplan, 2012; Cushing and van Vliet, 2016). Age-friendly and child-friendly cities approaches emphasize the role of the built environment in addressing the vulnerability of urban youth and older adults and have been endorsed by the WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (Manchester and Facer, 2017). Some scholars argue, however, that these two approaches have not converged in practice, often prioritizing the needs of a single age-group rather than embracing shared interests across the age spectrum (Biggs and Carr, 2015; Manchester and Facer, 2017).

IPS approaches bridge age- and child-friendly cities approaches to produce public spaces that support the needs of and foster relationships among different age groups (Biggs and Carr, 2015; Kaplan et al., 2020). They are distinct from monogenerational and multigenerational approaches as they seek to create shared spaces that address age-based needs, but also support meaningful interaction among different age groups (Kaplan et al., 2007; Thang and Kaplan, 2012). Scholars have shown that intergenerational interaction in public space may confer direct benefits to immediate participants and indirect community benefits (Cushing and van Vliet, 2016), including enhancing individual health and wellbeing (Haider, 2007; Dawson, 2017), fostering social inclusion, solidarity, and shared understanding (Lang, 1998; Scharlach and Lehning, 2013; Cortellesi and Kernan, 2016), and mobilizing shared interests and capacities toward the development of sustainable communities (Pain, 2005; Brown and Henkin, 2018).

Scholars studying IPS caution that success requires more than co-located community and recreational facilities and programs for youth and older adults. The framework of "intergenerational contact zones" has emerged as a means of translating the goals of IPS into practice, moving beyond co-location to creating interactive environments for youth and older adults (Thang, 2015; Kaplan et al., 2020). The literature presents design, procedural, and policy approaches to support generational interaction in public space. These include environmental design recommendations, such as offering tranquil spaces of retreat (Kaplan et al., 2007; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2016) and integrating activity spaces and features that provide a range of interests for different users (Larkin et al., 2010; Layne, 2009; Nelischer and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022).

The process through which IPS is created is important to their success; participatory processes engaging users of different ages in design, programming, and management may successfully balance the needs of different groups and foster a shared sense of responsibility and enthusiasm amongst users (Rigolon et al., 2015a; arki_lab, 2017; Sanchez and Stafford, 2020). Furthermore, scholars call for educating practitioners and policymakers on the benefits of intergenerational environments, encouraging approaches that avoid bureaucratic and professional siloes (Pain, 2005; van Vliet, 2011).

While primarily emerging out of disability activism and research, UD is akin to intergenerational approaches as it aims to produce built environments that support access and use by all ages and abilities (Biggs and Carr, 2015; Stafford and Baldwin, 2015). Given the alignment between these approaches, several studies suggest that UD and IPS approaches may be successfully integrated in public space design to better support the needs of people of different ages and abilities (Stafford and Baldwin, 2015; Lynch et al., 2018). Some scholars suggest that UD is considered a complement rather than a substitute to IPS approaches (Thang and Kaplan, 2012; Thang, 2015).

Hamraie

(2017, p. 184) emphasizes that early UD

framing viewed disability “in relation to other spatially excluded populations,

such as children, elderly people, and people of different sizes, whose needs

were often treated as ‘special’ or ‘exception’ rather than as integral to the

design of built space.” This view sees UD as a strategy for accountability

toward, and alliance between, multiple marginalized groups. “Ability” considers

the various ways in which bodies are differently abled, without losing sight of

the specific needs of groups whose experiences are different, including those

of disabled people. Mace and Lusher (1989) seek to leverage UD as a framework for

allyship among different marginalized groups whose concerns are ignored by

mainstream design standards. Age and disability are but a few of many

intersecting identities, along with

class, race, and gender, that can be highlighted within UD, rather than subsumed within a ‘post-disability’ discourse (Hamraie, 2017).

While much has been written about the benefits of IPS, most research continues to have a single-generational focus. The literature shows that few public spaces successfully integrate the needs of both older adults and youth, which can be partially explained by the lack of co-creation in the design process. Additionally, few studies examine IPS within historically disinvested neighbourhoods. Thus, pairing UD with IPS can cast light on the ways that barriers to participation experienced by youth, older adults, people with disabilities, along with other marginalized identities related to race, class, and gender, are complementary. We examine this proposition in our empirical study.

Research Design

Conceptual Framework

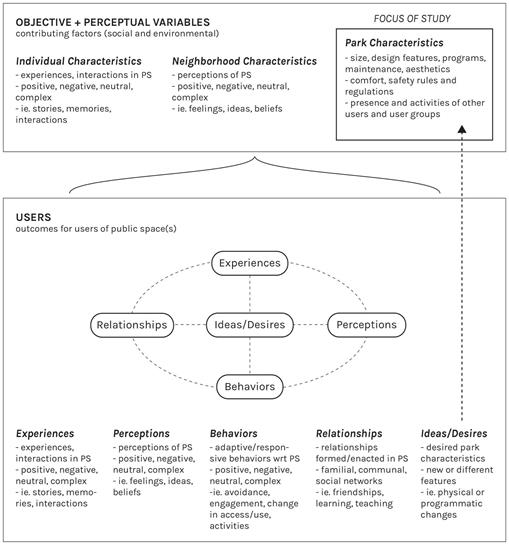

Figure 1. Study

Framework. Source: Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2021)

Our study’s conceptual framework (Figure 1) posits that a combination of objective and perceptual variables, which include users’ individual characteristics (age, ability, gender, income, race/ethnicity, place of residence), neighbourhood characteristics (street layout and connectivity, crime rates), and public space characteristics (size, design features, programming, regulations) influence experiences in public spaces. User public space experiences include their perceptions, behaviours/activities, relationships, and ideas/desires and should inform future public space interventions. Understanding the relationship between the objective and perceptual variables on the one hand, and user experiences in public spaces on the other, can yield important insights for planners and designers seeking to create IPS.

Research Questions

Two research questions guided our research:

- What are similarities and differences between older adults and youth in public space access and use in Westlake?

- How might UD and IPS frameworks complement one another to foster intergenerational exchanges in the public spaces of marginalized, multi-ethnic communities?

Context

Westlake, the densest Los Angeles neighbourhood, is located two miles west of downtown Los Angeles. It has about 120,000 residents, who are overwhelmingly renters (95%) and non-White (76.4%), and many are low-income (31.8% under the poverty line). Ten percent are older than 65, and 23 percent are younger than 18. Latinos constitute the largest racial/ethnic group (58%), but there are also significant numbers of Asian (primarily Korean) residents (29%) (ACS, 2019). The neighbourhood has two larger parks–MacArthur and Lafayette, as well as a recently-built pocket park, Golden Age Park. However, some older adults avoid these parks because of fear for their safety or because they do not fulfil their recreational and social needs. At the same time, the fear of crime makes parents apprehensive of allowing their youngsters to visit parks on their own (Author et al., 2009).

Our research involved a partnership with two community-based organizations with long histories and strong connections to the Westlake neighbourhood: St. Barnabas Senior Services (SBSS) and Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA). SBSS is one of the oldest senior-serving centres in Los Angeles. HOLA provides more than 2,200 underserved youth (aged 6-19) with free after-school programs. Partnering with SBSS and HOLA allowed us to recruit 43 youth and 38 older adult residents of Westlake, who participated in research activities and shared their experiences and ideas about the neighbourhood’s public spaces.[3]

Research Methods

We

employed structured site observations, focus group discussions, thick-mapping,

and participatory design workshops to identify similarities and differences

between the two

age-groups’ experiences and where their interests intersect. This information provided the basis for recommendations about public space in disinvested neighbourhoods. All activities, apart from observations and the participatory design exercise, were conducted on Zoom or UberConference, recorded, and transcribed.

Site observations: During October 2020, we undertook structured site observations at the three parks to inquire if and to what extent youth and older adults utilize them, what types of facilities they use, and if/how they interact with users of different generations. We visited each park six times during morning, afternoon, evening of both a weekday and a weekend, and conducted observations in 30-minute increments.

Focus groups: We conducted five focus groups of 90-120 minutes each. Each focus group had 6-8 participants, separated in age-specific groups (middle-schoolers, high-schoolers, Spanish-speaking older adults, English-speaking older adults, Korean-speaking older adults).[4] During the focus groups, we asked participants about their use of, experiences in, and attitudes about neighbourhood parks and public spaces before and during the pandemic. The focus groups concluded with a discussion of intergenerational parks and preferred public space activities and features.

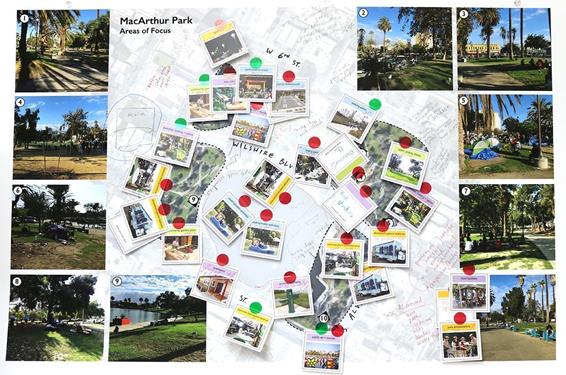

Thick-mapping: We conducted four “thick-mapping” workshops inviting participants to create a collective map (Figure 2) depicting their histories and emotional relationships to the public spaces, thus promoting a collective understanding of their meaning, significance, and opportunities for improvement. The created maps depicted information about daily travel routines, neighbourhood landmarks, positive and negative memories of neighbourhood public spaces, preferred park settings and activities, and suggestions for improvements.

In-depth interviews: We conducted twelve one-on-one, in-depth interviews with youth and older adults, approximately one hour each. Interviews began with general questions about life in Los Angeles, including how long the participant had lived in the city, daily life and routines before and during the pandemic, and issues facing Westlake. We asked participants about their relationship to the neighbourhood, its public spaces, and their hopes for the future of the neighbourhood and its parks.

Participatory design exercise: We invited participants to a final, two-hour participatory design exercise intended to collectively imagine future improvements in neighbourhood public spaces. We sought to engender an intergenerational dialogue and projective public space design discussion, and yield policy and design recommendations for IPS in Westlake. For this exercise, we set up “hybrid” (in-person and remote) participation options, which allowed for dialogue between those attending in-person and those on Zoom.

Challenges/Limitations: We had to switch some research tasks to a remote format because of COVID-19, which presented some challenges, including uneven internet access and lack of familiarity with digital interfaces amongst some participants. Youth

participants were more comfortable using video-conferencing tools like Zoom and more easily able to adapt to online research activities, whereas some older participants did not have access to Zoom or struggled to use it. This generational "digital divide" prompted us to adapt our activities to the needs and preferences of participants from different age groups, including hosting conversations with some older adults by phone-conferencing rather than Zoom.

Figure 2. Map of daily travel routines and landmarks named by research participants.

Source: Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2021)

Findings

Following our conceptual framework, we organize our findings according to participant experiences, perceptions, behaviours, and relationships, and conclude with stated needs and desires.

Experiences

Older adult participants shared personal memories and experiences in parks, often associated with the time they first arrived in Los Angeles. Youth similarly shared memories of the parks, based on their experiences visiting when younger or stories shared by their family and friends of what the parks were like in the past. Participants’ stories spoke to the role of public spaces in supporting diasporic identities and past feelings of belonging. For instance, one participant originally from El Salvador spoke about how he and others used to take care of one park: “People would come, bring food, and enjoy that the place was clean. I would tell them: ‘please, when you finish eating, take the garbage to the trash-container!’ But later people came to drink there, and fights happened, so we had to leave the place.”

Frequently, depictions of Westlake’s current public space assumed a darker quality than the remembered same space in the past. Several older adults and youth related recent experiences of harassment, unwanted attention, and assault in the parks, fostering a perception of danger and asking for enhanced park security. For some older adults, these fears were related to their age. As one participant shared, "As an older person, with a little push you can knock me down and take away what I have. So, for safety reasons, I don’t visit the park now.” For Korean American participants, fear of anti-Asian sentiment and violence hindered their public space use, which was exacerbated by the pandemic. According to one older adult, “Asians are in danger these days. ... I want to go to the park but I’m fearful. ... I’m always on guard, so it doesn’t feel good.” One young participant shared her experience of sexual harassment and unwanted touching at MacArthur Park: “There were always guys catcalling and whistling at me; it made me feel very unsafe.” A transgender youth also reported experiencing harassment. Such negative experiences tended to occur more at night and induced a fearful reaction to the neighbourhood’s public spaces.

Perceptions

Participants perceived the presence of other park users as positive or negative, depending on the user group and activity. A diversity of people coming together in public space was often framed positively by older adults, and associated with feelings of excitement, curiosity, and opportunities to learn from others. One older adult shared that she preferred Lafayette Park “because of the presence of both older and younger park users.” Some youth attributed their feelings of safety and fondness for Lafayette Park to the presence of children playing sports and the location of HOLA in the park. As one youth said, "at Lafayette, I feel really safe. I don’t know if it’s because I know all the staff there, or because it’s just a small park. Those factors contribute to the safety I feel there.”

Youth and older adults perceived unkempt or dirty areas as unsafe. Youth similarly expressed fear and discomfort in response to certain park conditions (trash, inadequate lighting, restrooms, presence of unhoused individuals) as well as overcrowding, harassment, or erratic behaviour by some unhoused individuals, particularly in MacArthur Park. Even youth, who had shorter memories of the neighbourhood, recalled hearing from family members about a time when the parks were better, and often shared the perception that park conditions had declined over time.

Behaviours

Focus groups, thick-mapping, and interviews revealed that many participants gravitate towards public spaces that have a level of familiarity, predictability, and features that accommodate their needs and interests. Youth participants were more likely to share an interest in sports and active recreation, and often preferred programmed spaces and active recreation facilities in the parks. Lafayette Park was where one youth participant scored their first soccer goal, another went to play basketball, and another enjoyed riding his scooter. Amongst older adults, walking, exercising, and people-watching were popular park activities.

The pandemic was a significant factor influencing behaviours and activities in parks and public spaces for both age groups. While some older adults continued to visit the parks, most emphasized that the pandemic had prevented them from visiting other public

spaces. One older adult shared, "I like exercising but couldn’t go to the YMCA. So, I just walked in the streets.” The youth reported spending more time at home as a result of the pandemic. Some visited parks less frequently, while others only at specific times to avoid crowding. Still the openness of the parks provided a respite from the virus. One male youth shared, “We go to the park because it’s very spacious. And that’s pretty good! Especially now.” Still some youth expressed disappointment with their inability to visit parks and participate in extracurricular activities during the pandemic, as well as concern about increased time spent indoors and behind screens. As one participant said, “We used to always walk, we always went outside to play, but now we’re inside - online school, more computers, more devices, which is unhealthy. But that’s my life now.”

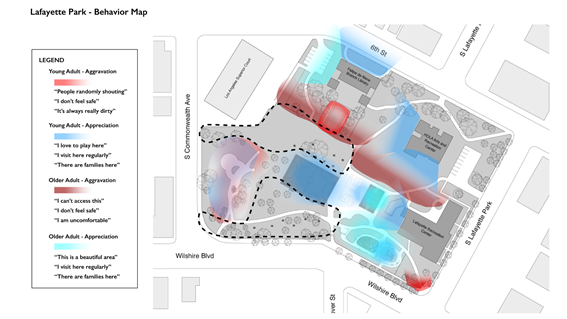

Additionally, concerns over cleanliness, presence of unhoused people, past negative experiences and interactions with other park users, and a perceived lack of safety influenced how and when youth and older adults visited the parks. Several participants reported avoiding certain park settings. One older adult noted her gender playing a role in the precautions she took, sharing that she was not comfortable visiting parks unaccompanied. The behaviours of participants indicating aggravation or appreciation for different parts of Lafayette Park are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Map of participant behaviours of Lafayette Park indicating areas of aggravation or appreciation. Source: Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2021).

Relationships

Memories of time spent at the parks with family and friends were prominent among youth participants. Speaking of Lafayette Park, one youth expressed nostalgia: “My uncles always rented out the soccer field, and I just sat there in the shade watching them play. It’s my favourite memory.” Many older adults recalled visiting the parks with family, particularly children and grandchildren, to walk or for birthdays, picnics, and

religious celebrations. One participant, who had spent 45 years working as a nanny, recalled how this role shaped how she understood and experienced the parks.

Youth were more likely to view visiting the park as a group activity, and several indicated feeling safer visiting the park with others. Conversely, most older adults visited the parks alone. For some, this lack of company was negative: "I used to walk with my friend for about 20 years. But that friend moved, so now I go alone. It’s boring walking alone.” Indeed, the opportunity to visit the park with friends was a motivating factor for some older adults’ visits. One of them, who had not been to Golden Age Park, suggested that she might visit it, if she had “somebody to go with.”

Relationships with community organizations were a major factor influencing how youth and older adults connected to the parks. Given its location at Lafayette Park, HOLA was frequently mentioned by youth in relation to their park use. Connecting HOLA with familiarity to the park and a sense of home, one participant shared, "I really like Lafayette Park! Every time I go there, I want to look at it more, because I’ve had so many experiences there since starting at HOLA. It just feels more like home!” Similarly, older adults frequently mentioned SBSS in relation to their experiences and interactions in neighbourhood parks.

Desires

Participants had many shared desires when it came to activities and features (Figure 4). Youth and older adults shared ideas they thought would appeal to both age groups. Gardens were one such amenity. As a youth stated, "We could utilize the park’s open space for flowers. I’ve heard older generations talk about how there were a lot of trees where they used to live, and now in the city, they miss trees and flowers.” Older adults expressed interest in yoga, music and dance classes, concerts, board games, art activities, and intergenerational language learning programs. One older adult mentioned: "Children speak English very well; I could learn English from them!” Another older adult expressed her desires of an intergenerational space as follows: “I would like a park with areas for children, young people, and seniors - a park that is for the family. I would enjoy having a cafeteria so that older adults can play domino. They can play shuffleboard; teens can play basketball, children can play on swings, and older people can watch the children play.”

Participants, regardless of age, emphasized their desire for cleaner and better maintained parks. Youth suggested strategies to improve cleanliness, including more waste receptacles, educational campaigns, public restroom cleaning, and park maintenance. One youth noted that park cleanliness may have broader benefits: “Cleanliness inspires and motivates people to be more inclusive at the park, because they know it’s safe for the family; it’s safer for them.” Another youth suggested that, “We can start by tackling the minor issues, such as garbage, and then work onto bigger issues like homelessness and poverty.” To make parks safer, youth and older adults suggested improving lighting at night and adding some fencing.

For both groups, age and physical ability were interrelated factors influencing their daily lives and relationship to neighbourhood public spaces. Several older adults reflected on mobility, independence, and autonomy, some indicating that their ability to visit parks had been constrained due to injuries, bad health, or disabilities. Improved amenities like safe and clean restrooms, drinking fountains, seating areas, and smooth walking paths were highlighted as features that would enable older adults to stay at the park longer.

They also saw more seating, park rangers, park programming, additional parking, and amenities like shaded pathways and coffee shops as actionable tasks that would attract older adults to the parks.

Intergenerational Space

Both groups welcomed the idea of park space designed to be more inclusive of diverse age groups. One youth emphasized how intergenerational parks could contribute to a sense of community: "More people can feel welcome to the park, motivated to go there. We’re all a community and should all feel welcome to the park!” An older adult shared, “I don’t have grandchildren, so I would love the interaction.” Several participants felt that intergenerational spaces could offer opportunities for people-watching, with one stating, "I so much enjoy seeing children play! It gives me great happiness.” However, one older adult was skeptical about the potential for non-familial intergenerational interaction in parks: "Do children like old people? They may like their own grandmas and grandpas, but they can’t like other grandmas and grandpas.”

Figure 4. Map of participant desires for creating intergenerational space in MacArthur Park. Source: Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2021)

Preferred Park Qualities

We asked participants to register their preferences along a set of continuums, which was developed based on park qualities that had emerged from prior participant interviews (Figure 5). Some younger and older participants preferred everyday park activities, while others privileged special events at the park. All but two participants preferred parks suitable for various age groups, rather than single-age users. This attribute garnered the greatest consensus among participants. Most participants in both age groups preferred spaces with specific programmatic and design features to informal park spaces. More older participants preferred enclosed spaces, while more younger participants preferred open spaces. This continuum yielded the clearest division of preferences by age. More participants preferred social rather than solitary park settings, with older adults showing stronger preferences. Somewhat surprisingly, more older adults than youth participants preferred active over tranquil park spaces. All elders preferred natural park spaces, while most youth preferred a balance between natural and built spaces in the parks. Surprisingly, the only votes for passive park spaces came from youth.

Figure 5. Continuum of park preferences. Source: Loukaitou-Sideris et al. (2021)

Occasionally, the preferences of one age group on a particular continuum appeared to conflict with the preferences of the same group on another, related continuum. For example, older adults expressed a preference for enclosed/private park spaces over open/public spaces, but later expressed preference for social/communal spaces over

solitary/intimate spaces. Older adults preferred structured/formal spaces to unstructured/informal spaces but also preferred natural spaces to human-built spaces. These seemingly contradictory preferences raise questions about the design of public spaces to meet user needs. For example, how can spaces be both social and enclosed/private? Additionally, what does both a structured/formal and natural environment look like? The results from this exercise indicate that the preferences of same-age participants may vary, and IPS must meet various needs and satisfy different choices. For example, a park should have both more private and enclosed settings, as well as settings that can accommodate more social and communal uses.

Discussion

The participants’ stories and responses reveal not only how different age groups may share common experiences and interests, but also how disability, race, or gender may intersect and influence preferences. Key themes that emerged included safety and inclusivity; complementarity and choice; and community bonds and place relationships.

Safety and Inclusivity

Safety, a common concern for many residents of disinvested neighbourhoods, was a key factor influencing the relationships of youth and older adults to public spaces in Westlake. Feelings of safety are affected by the physical and social characteristics of space. Inclusivity emerged as a related theme given that many participants expressed feeling unwelcome in public spaces due to their race, gender, age, or ability.

Both youth and older adults emphasized that lack of safety was a challenge in the neighbourhood and some of its public spaces. This perception affects their behaviour, often leading them to avoid public spaces or visit them only under certain conditions and times (with family, for programmed activities, during daylight). This also leads to a strong desire to address safety through a combination of policies, programming, and design.

The presence of unhoused individuals and gangs greatly contributed to participants’ feeling unsafe in the parks. Particularly older adults mentioned, homelessness frequently in our discussions, reflecting a wider social stigma that associates the experience of being unhoused with deviant behaviours. However, some participants expressed concern for the unhoused and wished that the city would find permanent housing for them.

Gender and race characteristics affected feelings of safety. Female participants referenced their gender as a reason for feeling unsafe visiting parks and public spaces. Similarly, one Asian-American participant cited the surge of anti-Asian sentiment due to the pandemic as a reason why she feared going to public spaces. These sentiments speak to larger issues of racialized and gendered risk and discrimination in public spaces, and the need to incorporate these concerns in their design and management.

In terms of the physical environment, the lack of cleanliness and maintenance of park infrastructure was cited as a reason why many participants avoided visiting Lafayette and MacArthur parks, while older adults mentioned the lack of restrooms as the reason why it was difficult for them to visit Golden Age Park. Such concerns speak to the need for investment in park upkeep.

Complementarity and Choice

That nearly all participants expressed enthusiasm about designing public spaces for intergenerational use and interaction is a key finding. This should embolden park designers to consider public spaces without the restrictive age-related assumptions that frequently characterize public space projects. For example, a park design driven by the stereotype that older adults prefer quieter, less active public spaces would ignore the desires of older adult participants in this research who also enjoy spaces of active engagement. Various design elements and programs that require active engagement would appeal to both elders and youth, such as community gardens, low-impact exercise machines, and walking paths. As mentioned by several older and younger participants, a coffee cart or coffee shop on the park grounds, a neighbourhood youth band that performs at the park, or a hub where park staff could meet and provide services to park users, are features that could attract intergenerational use. Similarly, the stereotype that youth only want to pursue active recreation in public spaces was proven incorrect in our discussions. We found that youth may also wish for quiet spaces to read, create art, or simply be by themselves. Park designers and managers should then strive to give choices to younger and older users and think about how activities in public spaces can complement, rather than impede one another.

This is not to suggest that age-specific park features should disappear. Child-specific playgrounds, for example, are an important feature for children’s development and allow younger children to feel engaged in public space; the provision of benches with back support and other comfortable seating opportunities are especially important for older adults. However, one can also consider playground equipment (such as low-impact exercise machines, interactive playgrounds), electronic games, and puzzles, that may be appealing to both older adults and youth. Our findings counter the idea that age-specific programming and design are mutually exclusive and support the idea that they can be complementary. Obviously, harmonious public space configurations are not always possible, but the idea of complementarity should imbue design approaches.

A related concept is the provision of choices and options. It is not only age, but also personal tastes and cultural traits that influence people’s needs and desires for certain environmental settings. Thus, providing different options and settings at the park, for example both quiet corners for reading but also more active and social spaces, would allow a diverse array of users to enjoy it.

Community Bonds and Relationships to Place

Our findings suggest that both youth and older adult perceptions and use of public space are mediated through personal and family histories and relationships, as well as their involvement with community institutions like schools, places of worship, and community non-profits (like HOLA and SBSS). Such relationships impact people’s sense of belonging to place (Tuan, 1977), and how they experience and use them. Bonds with community institutions and community-based groups can help overcome barriers to access and enable residents to make better use of public space resources. While participants overwhelmingly favoured the idea of IPS in their neighbourhood and shared similar visions for how to achieve such spaces, a barrier is the lack of programs or outlets that can foster intergenerational interaction. Community-based networks of friends, family, and non-profit organizations should be leveraged in creating programs with the specific intent of bringing together youth and older adults in public space

settings. Certain types of park programming would require more active collaboration between residents, non-profits, and city officials. The idea of a “park ambassador” who could facilitate user experiences and provide park information and a sense of security to park users[5] was popular among participants; and would require a program facilitated by the city and coordinated by local organizations.

Community bonds and relationships to place hold the power to enact change at a macro level (Hayden, 1995). Early framings of UD suggest that alliances should be formed across groups who have been similarly marginalized by design. They include youth, older adults, persons with disabilities, and others who have been oppressed because of their identity. As such, the needs of unhoused individuals, some of whom are seniors or youth, should also be considered in the provision of public space.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Our research reaffirms the importance of public space in disinvested urban areas. The amenities provided by well-maintained, intentionally designed public spaces carry additional importance for low-income neighbourhoods such as Westlake. Additionally, the pandemic has reinforced the necessity of easy access to outdoor public spaces for public health. We conclude that leveraging the intersectional approach inherent to early frameworks of UD does three things for considering intergenerational spaces anew:

- It creates awareness of how multiple historically marginalized identities (including age, disability, gender, race, and class) intersect allowing for the building of coalitions and the identification of complementary approaches to the design of public space.

- It draws attention to the power relations embedded in place and the ways in which IPS must be considered alongside other issues like gentrification, displacement, and environmental justice.

- It calls for a participatory approach to designing public spaces; one that takes seriously the input and experiences of public space users.

Based on our findings, we adapt the seven principles of UD (Connell et al., 1997) to offer the following suggestions for planners and designers wishing to develop IPS in disinvested neighbourhoods.

Principle 1: Equitable Use

● Design should consider the cultural context of the neighbourhood and the history of the community.

● Aesthetic choices should not be imposed from the outside, but determined in conversation with local community members, based on their needs and desires.

● Public space investments should be pursued in collaboration with trusted community-based organizations.

● Public space improvements can be advocated in tandem with anti-eviction and anti-displacement efforts and advocacy for affordable housing.

Principle 2: Flexibility in Use

● Flexible public space should consider the ways in which amenities can provide complementary services to youth, older adults, and persons with disabilities, as well as a degree of choice among users.

● Social activities should be programmed with an eye to attract intergenerational uses. Activities that are age-specific should ensure there is something for everyone, so that different age groups can also ‘do their own thing,’ while in each other’s company.

Principle 3: Simple and Intuitive Use

● Public signage in diverse languages is important in linguistically diverse communities.

● Infrastructural amenities like exercise machines, playgrounds, and community gardens should be easy to use with little required knowledge or experience. Community non-profit organizations can play a role in facilitating their use.

Principle 4: Perceptible Information

● All public space features should be easily perceptible, particularly for older adults experiencing age-related disabilities, and children who may not have yet comprehensive abilities that allow full use of public spaces.

● Users should not be left without assistance, should they desire it. Programmed activities led by park ambassadors may assist public space users and help establish a sense of community and shared public space ownership.

Principle 5: Tolerance for Error

● Infrastructural upkeep is essential to minimize safety hazards and attract users of all ages.

● Better lighting can possibly protect individuals from falls and crime incidents.

Principle 6: Low Physical Effort

● Shaded areas, availability of drinking water, comfortable seating, and clean public restrooms ensure that users, especially older adults, can easily visit public spaces and remain comfortable.

Principle 7: Size and Space for Approach and Use

● Sidewalks connecting neighbourhood public spaces should be well-maintained so that youth and older adults, particularly those with disabilities, can safely access them. Better access can also be achieved by locating public transit stops near parks.

In conclusion, our cities and their disinvested neighbourhoods face an urgent need for public spaces that support residents of diverse life stages and abilities. UD and IPS models provide useful frameworks for designing and programming such spaces. These models become more powerful if combined with participatory design approaches, that leverage multiple analytic tools, including traditional interview-based instruments alongside innovative visual instruments like thick mapping and participatory design. Additionally, partnerships and collaborations between planner, designers, and

community-based institutions, including those representing younger and older persons, persons with disabilities, and other historically marginalized groups, are critical to making our cities and their public spaces more inclusive.

References

AARP, 8 80 Cities and The Trust for Public Land (2018) Creating Parks and Public Spaces for People of All Ages, AARP.

American Community Survey (2019) Westlake Demographic Profile, Washington DC: US Bureau of the Census.

arki_lab (2017) A short guide to how to design intergenerational urban spaces. Copenhagen, Denmark. https://issuu.com/arki_lab/docs/a_short_guide_to_how_to_design_age.

Biggs, S. and Carr, A. (2015) ‘Age- and Child-Friendly Cities and the Promise of Intergenerational Space’, Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(1), 99–112.

Boone, C.G. Buckley, G.L., Grove, J.M. and Sister, C. (2009) ‘Parks and people: An environmental justice inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 99(4), 767–787.

Brown, C. and Henkin, N. (2018) ‘Communities for all ages: Reinforcing and Reimagining the Social Compact’, in Stafford, P.B. (ed.) The Global Age-Friendly Community Movement: A Critical Appraisal. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 139–168.

Byrne, J. (2012) ‘When green is white: The cultural politics of race, nature and social exclusion in a Los Angeles urban national park’, Geoforum, 43(3), 595–611.

Byrne, J. and Wolch, J. (2009) ‘Nature, race, and parks: past research and future directions for geographic research’, Progress in Human Geography, 33(6), 743–765.

Carstensen, L. (2016) ‘Hidden in Plain Sight: How Intergenerational Relationships Can Transform Our Future’. Stanford University: Stanford Center for Longevity.

Cortellesi, G. and Kernan, M. (2016) ‘Together Old and Young: How Informal Contact between Young Children and Older People Can Lead to Intergenerational Solidarity’, Studia paedagogica, 21(2), 101–116.

Crenshaw, K. (1991) ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color’, Stanford Law Review, 43(6), pp. 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039.

Cushing, D.F. and van Vliet, W. (2016) ‘Intergenerational Communities as Healthy Places for Meaningful Engagement and Interaction’, in Punch, S., Vanderbeck, R., and Skelton, T. (eds) Families, Intergenerationality, and Peer Group Relations. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 1–27.

Dawson, A.T. (2017) Intergenerational programming on a multi-generational play park and its impact on older adults. Master’s Thesis. University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Haider, J. (2007) ‘Inclusive design: planning public urban spaces for children’, in Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Municipal Engineer, 83–88. doi:10.1680/muen.2007.160.2.83.

Hamraie, A. (2017) Building access: universal design and the politics of disability. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hayden, D. (1995) The power of place: urban landscapes as public history. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Heynen, N., Perkins, H.A. and Roy, P. (2006) ‘The Political Ecology of Uneven Urban Green Space: The Impact of Political Economy on Race and Ethnicity in Producing Environmental Inequality in Milwaukee’, Urban Affairs Review, 42(1), 3–25.

Kaplan, M. Haider, J., Cohen, U. and Turner, D. (2007) ‘Environmental Design Perspectives on Intergenerational Programs and Practices: An Emergent Conceptual Framework’, Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 5(2), 81–110.

Kaplan, M., Thang, L.L., Sánchez, M. and Hoffman, J. (2020) ‘Introduction’, in Kaplan, M. et al. (eds) Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging. New York: Routledge.

Lang, F.R. (1998) ‘The young and the old in the city: Developing intergenerational relationships in urban environments’, in Görlitz, D. (ed.) Children, cities, and psychological theories: developing relationships. Berlin: de Gruyter, 598–628.

Larkin, E., Kaplan, M.S. and Rushton, S. (2010) ‘Designing Brain Healthy Environments for Intergenerational Programs’, Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 8(2), 161–176.

Layne, M.R. (2009) Supporting Intergenerational Interaction: Affordance of Urban Public Space. Doctoral Dissertation. North Carolina State University.

Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation (2016) Los Angeles Countywide Comprehensive Parks & Recreation Needs Assessment. Los Angeles, CA. Available at: https://lacountyparkneeds.org/final-report/.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Brozen, M. and Levy-Storms, L. (2014) Placemaking for an Aging Population: Guidelines for Senior-Friendly Parks. UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/450871hz.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Levy-Storms, L, Chen, L, and Brozen, M. (2016) ‘Parks for an Aging Population: Needs and Preferences of Low-Income Seniors in Los Angeles’, Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(3), 236–251.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. and Sideris, A. (2009) ‘What Brings Children to the Park? Analysis and Measurement of the Variables Affecting Children’s Use of Parks’, Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(1), 89–107.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. and Stieglitz, O. (2002) ‘Children in Los Angeles parks: A study of equity, quality and children’s satisfaction with neighborhood parks’, Town Planning Review, 73(4), 467–488.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Wendel, G, Bastar, G., Frumin, Z., and Nelischer, C. (2021) Creating Common Ground: Opportunities for Intergenerational Use of Public Spaces in Disinvested Communities, unpublished report. UCLA: cityLAB and Lewis Center for Regional Policy. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4674f4bz.

Low, S. and Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2020) Public Spaces for Older Adults Must be Reimagined as Cities Reopen. Available at: https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/public-spaces-for-older-adults-must-be-reimagined-as-cities-reopen (Accessed: 13 January 2022).

Lusher, R. and Mace, R. (1989) ‘Design for Physical and Mental Disabilities’, in Wilkes, J.A. and Packard, R.T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Architecture: Design Engineering and Construction. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 755.

Lynch, H. Moore, A., Edwards, C. and Horgan, L. (2018)Community Parks and Playgrounds: Intergenerational Participation through Universal Design. National Disability Authority. http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.2.22422.60486 (Accessed: 25 December 2020).

Mace, R.L., Hardie, G.J. and Place, J.P. (1991) Accessible Environments: Toward Universal Design.

Raleigh, N.C.: The Center for Universal Design.

Macedo, J. and Haddad, M.A. (2016) ‘Equitable distribution of open space: Using spatial analysis to evaluate urban parks in Curitiba, Brazil’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(6), 1096–1117.

Manchester, H. and Facer, K. (2017) ‘(Re)-Learning the City for Intergenerational Exchange’, in Sacré, H. and De Visscher, S. (eds) Learning the City: Cultural Approaches to Civic Learning in Urban Spaces. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Nelischer, C. and Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2022). ‘Intergenerational public space design and policy: A review of the literature,’ Journal of Planning Literature, doi:10.1177/08854122221092175.

Pain, R. (2005) Intergenerational Relations and Practice in the Development of Sustainable Communities. International Center for Regional Regeneration and Development Studies (ICRRDS), Durham University.

Rigolon, A., Derr, V. and Chawla, L. (2015a) ‘Green grounds for play and learning: An intergenerational model for joint design and use of school and park systems’, in Sinnett, D., Smith, N., and Burgess, S. (eds) Handbook on Green Infrastructure: Planning, Design and

Implementation. Edward Elgar Publishing, 281–300.

Rigolon, A. and Németh, J. (2018) ‘A Quality Index of Parks for Youth (QUINPY): Evaluating urban parks through geographic information systems’, Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 45(2), 275–294.

Sanchez, M. and Stafford, P.B. (2020) ‘A toolkit for intergenerational contact zones application’, in Kaplan, M. et al. (eds) Intergenerational contact zones: place-based strategies for promoting social inclusion and belonging, New York: Routledge, 259–273.

Scharlach, A.E. and Lehning, A.J. (2013) ‘Ageing-friendly communities and social inclusion in the United States of America’, Ageing and Society, 33(1), 110–136.

Stafford, L. and Baldwin, C. (2015) ‘Planning Neighbourhoods for all Ages and Abilities: A Multi-generational Perspective’, in State of Australian Cities Conference 2015: Refereed Proceedings. State of Australian Cities Research Network, 1–16.

Tan, E.J. Rebok, G.W., Yu, Q., Frangakis, C.E., Carlson, M.C., Wang, T., Ricks, M., Tanner, E.K., McGill, S. and Fried, L.P. (2009) ‘The Long- Term Relationship Between High-Intensity Volunteering and Physical Activity in Older African American Women’, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 64B(2), 304-311.

Tan, P.Y. and Samsudin, R. (2017) ‘Effects of spatial scale on assessment of spatial equity of urban park provision’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 158, 139–154.

Thang, L.L. (2015) ‘Creating an intergenerational contact zone’, in Vanderbeck, R.M. and Worth, N. (eds) Intergenerational space. London & New York: Routledge, 17–32.

Thang, L.L. and Kaplan, M.S. (2012) ‘Intergenerational Pathways for Building Relational Spaces and Places’, in Rowles, G.D. and Bernard, M. (eds) Environmental Gerontology : Making Meaningful Places in Old Age. Springer Publishing Company, 225–251.

Tuan, Y. (1977) Space and place: the perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

United Nations (2006) “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” Treaty Series 2515 (December): 3. Article 9. General Comment 2.

United Nations (2017) New Urban Agenda. ISBN: 978-92-1-132731-1. Quito: United Nations Habitat III Secretariat. Available at: https://habitat3.org/documents-and-archive/new-urban-agenda/ (Accessed: 17 January 2022).

Vaillant, G.E. (2003) Aging Well: Surprising Guideposts to a Happier Life from the Landmark Harvard Study of Adult Development. Boston: Little Brown and Company.

van Vliet, W. (2011) ‘Intergenerational Cities: A Framework for Policies and Programs’, Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 9(4), 348–365.

Winick, B.H. and Jaffe, M. (2015) Planning aging-supporting communities. (PAS Report 579). Chicago, IL: American Planning Association.

Wolch, J.R., Byrne, J. and Newell, J.P. (2014) ‘Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities “just green enough”’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 125, 234–244.

Wolch, J.R., Wilson, J.P. and Fehrenbach, J. (2005) ‘Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: An equity-mapping analysis’, Urban Geography, 26(1), 4–35.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2007) Global age-friendly cities: a guide. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755

[1] This article expands upon an earlier unpublished study of ours sponsored by the UCLA Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research (Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2021).

[2] Over 100 million Americans are over 50, and 75 million are younger than 18. Among them, poverty impacts nearly 25 million aging people, and 16.5 million young people, and poverty rates are higher for women, African Americans, and Hispanics (ACS, 2019).

[3] This research was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB). For each research activity, participants were given a $25 gift card as appreciation for their participation.

[5] Park ambassadors are alternatives to authority figures such as police officers. For the most vulnerable park users, they can serve as “trust agents” who help those seeking assistance in the form of housing, food, needle exchange, mental health services, and other forms of support (Madison, 2020).